Digital twins can save lives and money

Digital twins of wind turbines, machines and buildings help researchers detect faults and wear before they develop into problems and accidents.

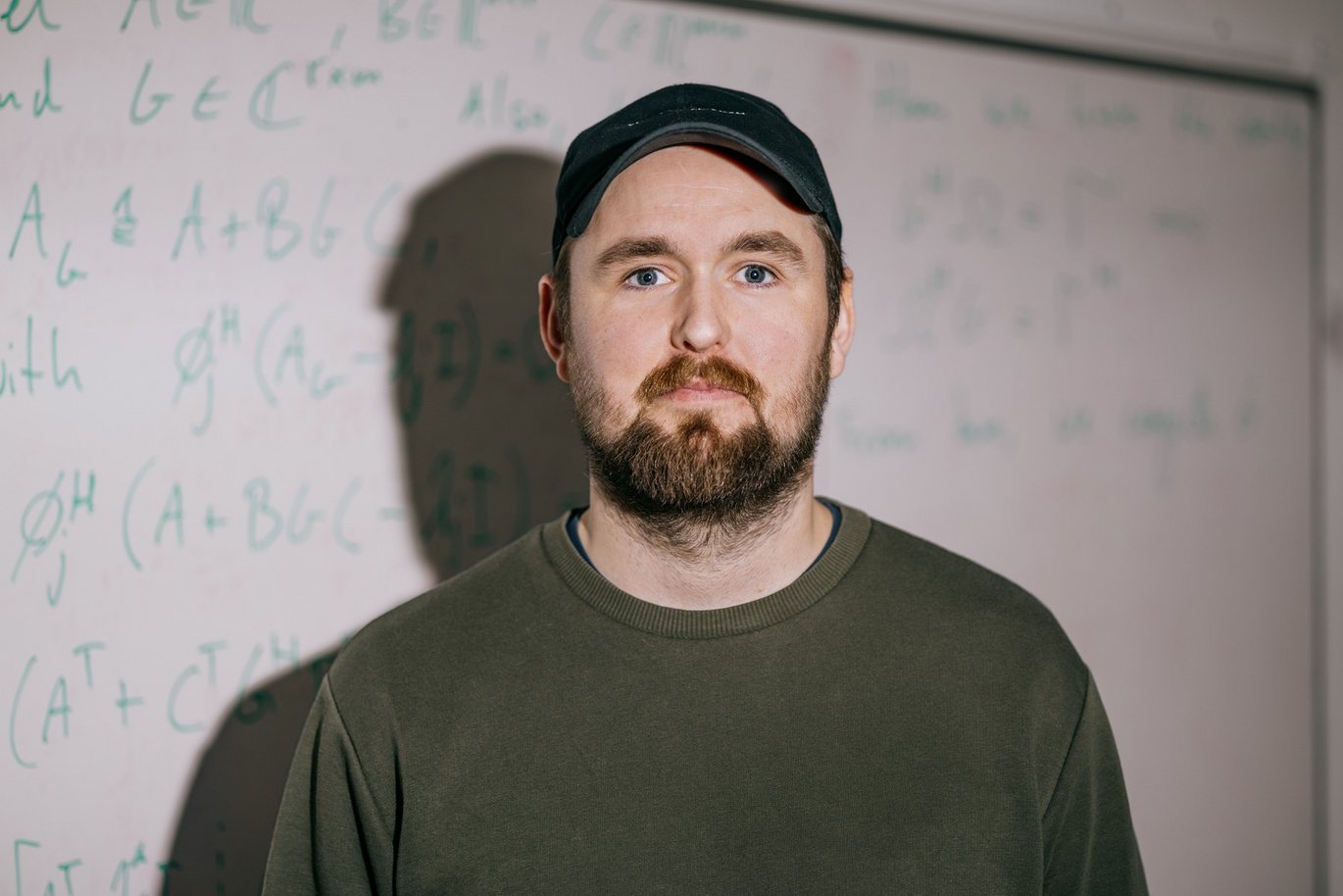

In a small, white, austere office in Katrinebjerg, Associate Professor Martin Dalgaard Ulriksen sits in front of his computer. He often sits here, because most of his work entails programming algorithms. At least when he’s not teaching aspiring engineers at Aarhus University.

Martin Dalgaard Ulriksen’s calculations form the basis for computer models – or digital twins, as they are also known – of wind turbines, ship engines and buildings. The models can predict when wear, extreme weather or other influences require parts to be inspected or replaced.

This can both prevent critical accidents and save companies a lot of money, he explains.

“I’m working on a project right now, where we're developing digital twins of wind turbines. As things stand today, wind turbine companies send technicians to inspect offshore and onshore turbines at fixed intervals – and that’s expensive.

With a digital twin, we’ll instead be able to predict when something actually needs to be inspected or repaired. And that will save a lot of money and hassle.”

Even though digital twins are in the spotlight right now, we’re still some way from seeing the technology fully implemented across society.

“We’re currently developing models and solutions that will allow us to create digital twins that match and sync as closely as possible with their physical counterparts,” says Martin Dalgaard Ulriksen.

Not just a digital copy

Digital twins are a buzzword in many engineering fields – and for good reason. The technology is predicted to make a wide range of tasks cheaper, safer and easier, especially within construction.

A digital twin is a kind of digital copy of, for example, a wind turbine, a building or an engine in the physical world.

But a digital twin is more than just a computer model. To qualify as a digital twin, the model needs both to receive data from its physical twin and to send messages back.

In other words, sensors must be installed in the physical twin to send data to the digital twin. Using this data, the digital twin can simulate various scenarios and predict when the risk of damage and accidents is likely to increase.

Technology can prevent serious accidents

Several bridges around the world have collapsed in recent years. Last year, the Carola Bridge over the Danube near Dresden collapsed. And in 2018 there was a terrible accident in Genoa, Italy. A 200-metre section of the Ponte Morandi bridge spanning the city collapsed, sending cars and lorries crashing down into the buildings below.

Without knowing the specific details of the accident, Martin Dalgaard Ulriksen believes that digital twins could help prevent such incidents in the future.

“While I don't work with bridges myself, the principle is the same as with wind turbines or engines. By fitting sensors at various locations on the bridge, and feeding data from the bridge into a digital twin, we’d be able to predict a collapse before it happens.”

Luckily, no one was on the Carola bridge when it collapsed. In Genoa, they weren't so lucky. 43 people died when the bridge collapsed.

“We believe that our technology could prevent this kind of accident. It could help optimise the scheduling of bridge inspections. Even basic data about the forces acting on the bridge throughout its lifetime is interesting. It will help us build better bridges in the future,” he says.

Together with a number of other researchers, Martin Dalgaard Ulriksen is responsible for research at the Department of Mechanical and Production Engineering into digital twins. The research area is known as System Dynamics.

His research includes several collaborative projects with industry partners. Currently, he is involved in projects in which he is collaborating with Hottinger Brüel & Kjær, Rambøll, Force Technology, Vestas Air Coil and Vienna Consulting Engineers.